Some years ago, I bought a plot of land in Prantik, a locality just beyond Tagore’s Viswabharati University in Santiniketan, West Bengal, India,1 and put up a little cottage on it. Houses in that area have no numbers to identify them – they are known by their names or the names of their owners. When it came to naming my house, after a lot of deliberation in the family, my mother suggested we name it Hermitage. My children were not too happy with it; they felt it was too puritanical. I had my reservations – it was to be a holiday home, filled with fun and laughter not with piety and saintliness and we thought Ma wanted to establish some sort of connection to Tagore’s Ashram – she is a die-hard admirer of the Tagore family and everything that they achieved.

But that, we soon realized, was not the case. Ma’s ancestral house in Cuttack had been called Hermitage. It had long been broken down or sold (nobody seems to know what happened!) and the name was also lost in the mists of time. Naming my house was Ma’s way of keeping “Hermitage” alive. She had spent many holidays in Cuttack and had very fond and happy memories of Hermitage and her time there with her cousins.

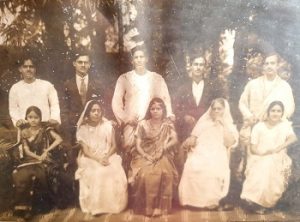

The original Hermitage was built by Ma’s paternal grandfather – Khirode Chandra Roy Chowdhury, who was born into the landed Sabarna Roy Chowdhury family of Barisha-Behala (24 Parganas) on September 17th, 1850.

Khirode Chandra’s father, Kalicharan Roy Chowdhury, was a man of straitened means and died when Khirode – the eldest of 5 siblings -was around 13 years old. As a result, he had a rather difficult and penurious childhood. Money was scarce. In an autobiographical article in later life in the periodical “Janmabhoomi”, he wrote- “The day my father died there was not a paisa in the house. And there were no friends or relatives either who bore the expenses of his last rites.”

Khirode Chandra was a very intelligent and talented student and throughout his student life received academic scholarships. Given that there was little money, he walked 14-15 miles every day to get to Hindu School and later, to Presidency College2. Despite these hardships, he obtained a First Division in his F.A. Exams from Presidency College and then stood first in his B.A. Honors Exams. In 1874 he successfully completed his Master’s degree in History again being ranked First in the University.

His academic achievements could have easily gained him a government job but he chose instead to become an educator. His entire life was spent in teaching and assiduously propagating and expanding the reach of education. He was not just an educator – he was an able administrator too as evidenced from his role as School Inspector. Besides this, he was a prolific writer, having authored many English, Bengali, Hindi and Oriya textbooks and innumerable essays. At his death, the July 4th, 1916 edition of the local newspaper, “Amrit Bazar Patrika” carried the following tribute – “He was one of the ablest headmasters and his pupils who can be counted by thousands are adorning different walks of life in Bengal, Behar and Orissa.”

Khirode Chandra taught at a large number of institutions and served as Headmaster of schools in Puri and Cuttack in the province of Orissa, and Bhagalpur and Chhapra in Bihar. He also served at the Government College and at Chittagong College. Later, he became the Principal of Ravenshaw College in Cuttack, the first Indian to occupy that position.

While in Chhapra District in Bihar, he started a school with a handful of students where in a short time, the numbers swelled to over 700. One of the students, Rajendra Prasad became independent India’s first President. In his autobiography – “Atmakatha” – Rajendra Prasad mentioned Khirode Chandra with immense respect.

The famous poet and playwright, lyricist and musician of Bengal, Dwijendralal Ray was another of his favourite students. Sujata Chowdhury, former principal of Lady Brabourne College, Calcutta and Khirode Chandra’s grand-daughter writes in her book “Mone Pore” – “ I have heard from my father that DL Ray would often times read out his compositions to Thakurdada before publishing them.”

Subhash Chandra Bose – later Netaji – was Khirode Chandra’s student when he was Principal of Ravenshaw School in Cuttack. Amita Malik, a well-known film critic and another grand-daughter of Khirode Chandra’s, writes in her memoirs -”Amita – No Holds Barred” – “When grandfather had a stroke, ice was urgently needed to bring down his temperature…young Subhash Bose volunteered to walk to the railway station which was at quite a distance, in the burning heat of Orissa’s dreaded summer to fetch a block of ice. My father remembered how Bose came back with an enormous block on his head ; his face was pink from heat and exertion.”

Apart from being an educator par excellence, Khirode Chandra’s contribution in the fields of literature and journalism was immense. He was deeply interested in a diverse range of subjects and wrote innumerable articles and essays on literature, history, and the science of knowledge. His “Aborigines of Bengal” is an extraordinary, ethnographical treatise. His book “Manab Prokriti” (Theory of Evolution ) was the first to talk about evolution in terms of scientific logic .It was the first book of its kind in India and was translated from the original Bengali into 9 other Indian languages. He was also considered a pandit in archaeology and antiquity.

His unbiased non-partisan nature and his deep love of literature drew him towards other religions and his essays on Vaishnavism, Buddhism and medieval poetry earned a tremendous amount of appreciation and respect. His interest in Vaishnavism and Vaishnav literature inspired him to compose “Premhaar” – a collection of Vaishnav thoughts.

Khirode Chandra was also a scholar and an authority on the Buddhist faith, scriptures and literature and published many articles on them. He was instrumental in initiating a study of and introducing a course on the Pali language in Calcutta University and Chittagong University. Prior to this Pali had never been taught at Calcutta University. In his personal life, he had a passion for collecting Buddha statues from different countries.

His articles, essays and critiques were published in range of newspapers and periodicals of his times – His articles highlighted his contemplative and idealist views and ideas. But his writings have been lost over time – it is impossible today to estimate either the number of these compositions or get access to them.

Khirode Chandra wrote a large number of biographical articles for “Nabyabharat” on the lives of many well known personalities of his time – Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar, Michael Madhusudan Dutta, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Rajendralal Mitra, Keshab Chandra Sen, Rajnarayan Basu among others, in an attempt to inspire, motivate and influence future generations.

Apart from writing for other publications, Khirode Chandra established his own printing press – Star Press – and was the publisher of two of his own newspapers – the English “Star of Utkal” (started in 1903) and the Bengali “Mrinmoyee”(started in 1909). Star of Utkal was Orissa’s first English newspaper. It started as a weekly paper and very soon it became a bi-weekly and then a few years prior to his demise it started being published thrice a week. In 1915, he decided to convert Star of Utkal into a daily newspaper.

Khirode Chandra was a fearless journalist and his articles were sharply critical of the colonial Government’s policies and functioning. He held the government responsible for the large scale starvation deaths of 1907-08 in the districts of Cuttack, Puri and Balasore. Towards the middle of 1915, the Bihar and Orissa Government, annoyed and irritated with the controversial writings in the Star of Utkal, sent a notice for a security demand of Rs 2000/ to the newspaper. Khirode Chandra refused to operate under this restriction. He shut down Star of Utkal. In an article titled “Adieu” in the last edition of the newspaper, he had written -”We would rather drown the Paper in the waters of the Bay of Bengal than work with a halter around the neck.”

A week after shutting down Star of Utkal, Khirode Chandra started teaching at Victoria High School, which had been established by his friend , the poet Madhusudan Rao. A while later he established Hindu College, an independent High School, at his own expense. Starting with just 4 students, in a few months the numbers swelled to nearly 300.

While still a student, Khirode Chandra was attracted to the principles and ideals of Brahmo movement. At that time, Keshab Chandra Sen, the leader, wielded a tremendous amount of influence on the educated segments of society. On August 22nd, 1869 (7th Bhadro in the Bengali calender), the day the Brahmo Samaj was established, Keshab Sen initiated 21 young men into Brahmoism by administering an oath. Khirode Chandra was one of them. The young Khirode Chandra became an active member of Brahmo Samaj3.

Khirode’s personal life was also rather interesting. Family lore has it that he married four times – Ma tells me that her mother (the late Bina Roy Chowdhury) used to say that if she had known that her father-in-law had married so many times, she would definitely not have married into the family ! But official records are somewhat kinder, crediting him with only two marriages. He had 7 children by his first wife – four sons and three daughters. After his wife’s death, in 1899, when he was 49 – at that time, he was considered to be quite elderly – he married Swarnalata, a widow with two daughters who was the daughter of Gunabhiram Barua, a leading educator and the pioneer of Brahmoism in Assam. He was not perturbed by societal criticisms of his actions and by marrying Swarnalata, not only did he carry forward the principles of the Brahmo Samaj but also set an example before all of Bengal and Orissa’s high class society.

On a more humorous note, at one point of time, there had been a suggestion of a marriage alliance between Swarnalata and Rabindranath Tagore. That proposal was rejected by Tagore’s father, Maharshi Debendranath Tagore, on the ground that she was the daughter of a widow who had remarried! (Swarnalata’s mother was a widow when Gunabhiram Barua married her). Strange, coming from one of the stalwarts and leading lights of the Brahmo Samaj that propagated widow remarriage. But be that as it may, Swarnalata married Khirode Chandra and her sons (my maternal grandfather the eldest among them) always bemoaned the fact that they had missed being Rabindranath Tagore’s sons by a mere whisker!

Khirode had six more children by this marriage – four sons and two daughters. But he did not live long enough to bring them up. He died when the eldest was just sixteen years old, leaving Swarnalata to manage the family and the household which she did admirably – hers is another story, for another time! A great supporter of women’s education, all his daughters were highly educated and professionally qualified.

On 29th June 1916, he had an epilepsy attack and died on the morning of June 30th.

Khirode Chandra’s idealism and liberal mindset, his scientific bent of mind and rationalism, his interest in and pursuit of knowledge about a varied and diverse range of subjects, his untiring efforts to promote education, his love and respect for his students and his contemporaries, his literary and journalistic abilities, his uncompromising support of what was true and right, all make him a genuine embodiment of the 19th century enlightenment even though most of his achievements are lost in the mists of time.

Information for this article has been gleaned from Rina Nandy’s (Khirode Chandra’s youngest grand-daughter) tribute to him on his 100th death anniversary (which was in turn based on the writings of Haradhan Dutta in his book – Shekaler Shikkhaguru) and from Pronob Roy Chowdhury’s (Khirode Chandra and Swarnalata’s 3rd son) writings and from conversations with family members. Unfortunately, Khirode Chandra’s children rarely spoke about their parents to their children or grandchildren, so we know very little personal details.

[2] A 19th century religious reform movement

Sumita Sen divides her time between New Delhi and Kolkata.

Footnotes

- Rabindranath Tagore, poet and author who was awarded the nobel prize for literature in 1913, establish a school that later became a University in 1921

- Two of the oldest institutions in Calcutta

- A 19th century religious reform movement in Bengal

Loved the story!